Tư liệu và nghiên cứu

visibility 277 lượt xem calendar_month 11/01/2024

Oyster shell glaze evokes a golden era

A unique style of pottery glaze indigenous to Phu Yen has been rediscovered. But though it flourished for centuries, there is no possibility it can be revived.

Oyster shell glaze evokes a golden era

Oyster shell glaze evokes a golden era

Surfing the Smithsonian online gallery, one can find a handful of ceramic objects from Tuy Hoa in Central Viet Nam.

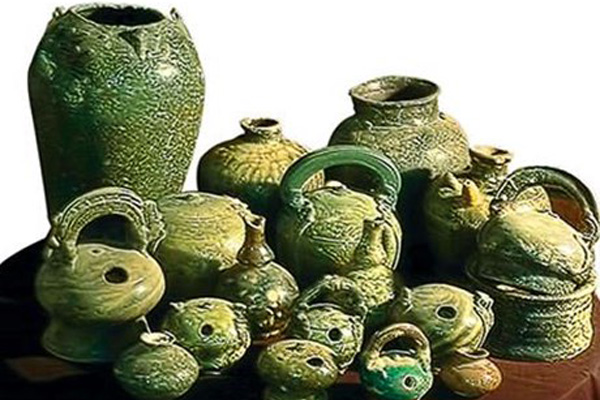

The items, including a lime-paste pot, a big jar and a gourd-shaped bottle are the gallery’s ceramic highlights from mainland Southeast Asia. They are dated somewhere between 18th and mid-20th centuries, and their glaze has been determined to be a kind of alkali-silicate.

Located near Tuy Hoa City, which is the capital of central Phu Yen Province, Quang Duc is one of two villages that are listed among 36 old ceramic production sites in the nation by Ha Noi-based Museum of Fine Arts.

Until recently, little was known about the village including its exact location and what kind of pottery it produced.

In a shipwreck recently salvaged offshore Binh Thuan Province, among thousands of local and Chinese ceramics dating back around 400 years ago were items whose surfaces carried rough marks.

"They definitely belong to Quang Duc Village," said 40-year-old collector Tran Thanh Hung, a native of Phu Yen, who went to the site to film the wreck himself. "The rough marks are their signature."

Hung, a reporter at the local television station, is probably the most avid collector of this kind of pottery and the first contact for any one interested in it.

However, Hung conceded that he did not know immediately that these potteries were made in a village just adjacent to his native place.

"I stumbled across this jar during a field trip to an E-de [an ethnic group] village in 1993," Hung said, pointing to a 60cm tall jar in his room.

"I was bewitched by its quaintness and couldn’t leave without begging the chieftain to sell it to me," he said, noting that the chieftain could only explain to him that the jar was made in a village named Lo Gom around Tuy Hoa.

"I know the village like the back of my hand, because I’ve grown up around the area, but I was surprised to know this stunning jar was made there."

Hung then learned that some HCM City collectors had also acquired similar items, which they said were retrieved from the bottom of tributaries of the Sai Gon and Mekong rivers. But they could not identify the pottery.

"So one day I got back to the village and the villagers, most of whom knew nothing about pottery, referred me to Nguyen Thinh, one of the elders.

"Fortunately, Thinh was the last witness to this craft," Hung said, adding that the old man opened the world to a hitherto forgotten heritage.

"The village was once called Quang Duc," said Thinh, 85, of what is today known as Lo Gom, nestled at the foot of the A Man Mountain, overlooking a river intersection 30km to the north of Tuy Hoa.

Thinh was just a little boy when the whole village was engaged in making pottery, he said, adding there were around 10 kilns used.

Main products included chat (large water container), choe (tall wine jar), binh voi (pot to hold lime-paste essential in betel quids) and hoa lo (heater), said Thinh, who has been bedridden for 18 months because of a stroke.

"We worked day and night, but still could not meet demand," said Thinh’s wife, Phan Thi Ba, 84, noting that traders accessed the village both by river and by land, turning it into a busy trading hub that sent pottery items nationwide.

The village even got orders from kings to make bonsai containers to be placed inside Hue citadels, Ba said. Ba worked as a potter after she got married.

The vocation is still evidenced by a small temple in the village worshipping the ancestor who introduced the craft, and two kilns that are still working.

However, Thinh cannot tell when this vocation arrived in the village. He learned the craft from his grandfather who had the skills handed down by his own grandfather who moved here from Binh Dinh Province.

Today, Thinh, Ba and his cousin Nguyen Dan, 84, are the last villagers still holding the secrets of Quang Duc ceramics, but they’re too infirm to walk steadily, let alone lay hands on clay.

The business thrived until it was disrupted by bombing almost 50 years ago that sent everyone fleeing, Thinh recalled. Thinh said he did resume production on a smaller scale after the war until 1983, when he stopped it for good because of poor demand.

"People opted for plastic which is more convenient than stoneware," he said.

"What do they make lime-paste pots for? No one is chewing betel anymore," replied Ba when asked why the remaining two kilns were turning out earthenware so different from their predecessors.

"The potters now are too young to know the intricacies," she said.

What charmed me the most about Quang Duc glazed relics is that they are so shiny and smooth to touch.

Unearthed

"This was not glazed like that of chinaware," Ba said, pointing to a pot unearthed at a construction site in her backyard, which was still glossy despite being buried in the earth for hundreds of years, according to Thinh’s estimates.

"In fact, it was the oysters shells melted in the heat of more than 1,000C that gave the pots such a glaze," she explained.

Ba said oysters were once abundant in nearby O Loan Lagoon, providing potters with a wealth of shells, which ‘were placed at the bottom, inside and around and wedged between the items.’

"The glaze would come only if shells were adequately heated within 24 hours," she elaborated, "and that job could be done only by using mang lang firewood."

Mang lang used to be widely available in the mountains around the area, Ba remembered.

However, both Thinh and Ba could not explain why white shells could turn out a variety of glazed colours including aquamarine, azure, black and auburn.

Hung attributes the effect to different kinds of clay, which was taken from nowhere else but nearby An Dinh Village, according to Thinh.

In fact, as big as they are, the jars in Hung’s collection are light but solid, thanks to the kind of clay.

Although Thinh’s kiln was already levelled up, vestiges of a busy ceramic workshop can still be seen in his backyard with lots of shards and shells and discarded products scattered everywhere.

"Oyster shells explain why any glazed pottery made here have such distinct rough marks, which are actually remnants of shells stuck to potteries," Hung said.

"We’ve got enough evidence to prove that the uniquely glazed pottery was made right here, and that this is the renowned Quang Duc Village mentioned in old books," said Hung, who is on a mission to recover Quang Duc pottery.

However, "the missing link" is to determine its origin and get an explanation for the different colours shed by the melted shells.

"In my opinion, it’s likely that Quang Duc succeeded Go Sanh pottery in Binh Dinh, given that Thinh’s forefathers immigrated from the province," he said, conceding that the craft was "irreversibly extinct".

"No clay, no shells, no firewood, and especially, no skilled workers," Thinh said.

"We’re barred from taking clay from paddy fields, whilst mang lang firewood and oysters are no longer available," Thinh lamented.

"What’s more, all the equipment was donated to museums, and youngsters do not bother to stay bowed all day to learn the craft," he said.

For his part, Hung said he is looking forward to producing an illustration book and getting exhibition space on the Mountain in Tuy Hoa Town featuring Quang Duc pottery.

This is apart from the Con Duong Dat Nung [A Road of Earthenware] show early next year in Ha Noi to celebrate the capital’s millenium.

"Unlike other ceramic or chinaware that are mainly used as luxury items in palaces and mansions, Quang Duc pottery is intended for popular use, so they carry a human soul," he said. — VNS

The items, including a lime-paste pot, a big jar and a gourd-shaped bottle are the gallery’s ceramic highlights from mainland Southeast Asia. They are dated somewhere between 18th and mid-20th centuries, and their glaze has been determined to be a kind of alkali-silicate.

Located near Tuy Hoa City, which is the capital of central Phu Yen Province, Quang Duc is one of two villages that are listed among 36 old ceramic production sites in the nation by Ha Noi-based Museum of Fine Arts.

Until recently, little was known about the village including its exact location and what kind of pottery it produced.

In a shipwreck recently salvaged offshore Binh Thuan Province, among thousands of local and Chinese ceramics dating back around 400 years ago were items whose surfaces carried rough marks.

"They definitely belong to Quang Duc Village," said 40-year-old collector Tran Thanh Hung, a native of Phu Yen, who went to the site to film the wreck himself. "The rough marks are their signature."

Hung, a reporter at the local television station, is probably the most avid collector of this kind of pottery and the first contact for any one interested in it.

However, Hung conceded that he did not know immediately that these potteries were made in a village just adjacent to his native place.

"I stumbled across this jar during a field trip to an E-de [an ethnic group] village in 1993," Hung said, pointing to a 60cm tall jar in his room.

"I was bewitched by its quaintness and couldn’t leave without begging the chieftain to sell it to me," he said, noting that the chieftain could only explain to him that the jar was made in a village named Lo Gom around Tuy Hoa.

"I know the village like the back of my hand, because I’ve grown up around the area, but I was surprised to know this stunning jar was made there."

Hung then learned that some HCM City collectors had also acquired similar items, which they said were retrieved from the bottom of tributaries of the Sai Gon and Mekong rivers. But they could not identify the pottery.

"So one day I got back to the village and the villagers, most of whom knew nothing about pottery, referred me to Nguyen Thinh, one of the elders.

"Fortunately, Thinh was the last witness to this craft," Hung said, adding that the old man opened the world to a hitherto forgotten heritage.

"The village was once called Quang Duc," said Thinh, 85, of what is today known as Lo Gom, nestled at the foot of the A Man Mountain, overlooking a river intersection 30km to the north of Tuy Hoa.

Thinh was just a little boy when the whole village was engaged in making pottery, he said, adding there were around 10 kilns used.

Main products included chat (large water container), choe (tall wine jar), binh voi (pot to hold lime-paste essential in betel quids) and hoa lo (heater), said Thinh, who has been bedridden for 18 months because of a stroke.

"We worked day and night, but still could not meet demand," said Thinh’s wife, Phan Thi Ba, 84, noting that traders accessed the village both by river and by land, turning it into a busy trading hub that sent pottery items nationwide.

The village even got orders from kings to make bonsai containers to be placed inside Hue citadels, Ba said. Ba worked as a potter after she got married.

The vocation is still evidenced by a small temple in the village worshipping the ancestor who introduced the craft, and two kilns that are still working.

However, Thinh cannot tell when this vocation arrived in the village. He learned the craft from his grandfather who had the skills handed down by his own grandfather who moved here from Binh Dinh Province.

Today, Thinh, Ba and his cousin Nguyen Dan, 84, are the last villagers still holding the secrets of Quang Duc ceramics, but they’re too infirm to walk steadily, let alone lay hands on clay.

The business thrived until it was disrupted by bombing almost 50 years ago that sent everyone fleeing, Thinh recalled. Thinh said he did resume production on a smaller scale after the war until 1983, when he stopped it for good because of poor demand.

"People opted for plastic which is more convenient than stoneware," he said.

"What do they make lime-paste pots for? No one is chewing betel anymore," replied Ba when asked why the remaining two kilns were turning out earthenware so different from their predecessors.

"The potters now are too young to know the intricacies," she said.

What charmed me the most about Quang Duc glazed relics is that they are so shiny and smooth to touch.

Unearthed

"This was not glazed like that of chinaware," Ba said, pointing to a pot unearthed at a construction site in her backyard, which was still glossy despite being buried in the earth for hundreds of years, according to Thinh’s estimates.

"In fact, it was the oysters shells melted in the heat of more than 1,000C that gave the pots such a glaze," she explained.

Ba said oysters were once abundant in nearby O Loan Lagoon, providing potters with a wealth of shells, which ‘were placed at the bottom, inside and around and wedged between the items.’

"The glaze would come only if shells were adequately heated within 24 hours," she elaborated, "and that job could be done only by using mang lang firewood."

Mang lang used to be widely available in the mountains around the area, Ba remembered.

However, both Thinh and Ba could not explain why white shells could turn out a variety of glazed colours including aquamarine, azure, black and auburn.

Hung attributes the effect to different kinds of clay, which was taken from nowhere else but nearby An Dinh Village, according to Thinh.

In fact, as big as they are, the jars in Hung’s collection are light but solid, thanks to the kind of clay.

Although Thinh’s kiln was already levelled up, vestiges of a busy ceramic workshop can still be seen in his backyard with lots of shards and shells and discarded products scattered everywhere.

"Oyster shells explain why any glazed pottery made here have such distinct rough marks, which are actually remnants of shells stuck to potteries," Hung said.

"We’ve got enough evidence to prove that the uniquely glazed pottery was made right here, and that this is the renowned Quang Duc Village mentioned in old books," said Hung, who is on a mission to recover Quang Duc pottery.

However, "the missing link" is to determine its origin and get an explanation for the different colours shed by the melted shells.

"In my opinion, it’s likely that Quang Duc succeeded Go Sanh pottery in Binh Dinh, given that Thinh’s forefathers immigrated from the province," he said, conceding that the craft was "irreversibly extinct".

"No clay, no shells, no firewood, and especially, no skilled workers," Thinh said.

"We’re barred from taking clay from paddy fields, whilst mang lang firewood and oysters are no longer available," Thinh lamented.

"What’s more, all the equipment was donated to museums, and youngsters do not bother to stay bowed all day to learn the craft," he said.

For his part, Hung said he is looking forward to producing an illustration book and getting exhibition space on the Mountain in Tuy Hoa Town featuring Quang Duc pottery.

This is apart from the Con Duong Dat Nung [A Road of Earthenware] show early next year in Ha Noi to celebrate the capital’s millenium.

"Unlike other ceramic or chinaware that are mainly used as luxury items in palaces and mansions, Quang Duc pottery is intended for popular use, so they carry a human soul," he said. — VNS

Xem nhiều nhất

Khai mạc triển lãm “Từ gốm Gò Sành đến gốm Quảng Đức”

(BĐ) - Chiều qua (24.7), tại Bảo tàng Gốm cổ Gò Sành Vijaya Chămpa Bình Định (TP. Quy Nhơn), đã khai mạc triển lãm chuyên đề “Từ gốm Gò Sành đến gốm Quảng Đức”.

QUẢNG ĐỨC – LÀNG GỐM CỔ BÊN BỜ SÔNG CÁI

Lâu nay, giới chơi cổ vật thường nhắc đến một dòng gốm cổ với nhiều nét riêng độc đáo có nguồn gốc từ làng Quảng Đức,

Từ Gò Sành đến Quảng Đức

Chúng ta đang xuôi dòng sông Kôn để đến một trong những vùng quê thanh bình của vùng đất võ trời văn Bình Định. Ấy là miền gốm cổ Gò Sành tại thôn Phụ Quang, xã Nhơn Hoà huyện An Nhơn. Bên dòng sôn

Oyster shell glaze evokes a golden era

A unique style of pottery glaze indigenous to Phu Yen has been rediscovered. But though it flourished for centuries, there is no possibility it can be revived.

Nhà nghiên cứu Suzuki Tomomi: Gốm nung làm rung động trái tim tôi

Chiều chớm xuân bên dòng sông Ba soi bóng phố thị Tuy Hòa, Suzuki Tomomi, người Nhật Bản, say sưa phác họa lại chuyến điền dã từ Đà Nẵng đến Phú Yên để được tận mắt chiêm ngưỡng những kiệt tá

Dấu Ấn Trong Lòng Đất

Cuộc triển lãm đó đã qua gần 1 năm, vậy mà âm hưởng vẫn còn lưu lại tới ngày nay. Năm 2008, triển lãm gốm cổ “Từ Gò Sành đến Quảng Đức” đã mở ra một mạch tư tưởng lớn để hậu thế có

Tin mới nhất

Từ Gò Sành đến Quảng Đức

Chúng ta đang xuôi dòng sông Kôn để đến một trong những vùng quê thanh bình của vùng đất võ trời văn Bình Định. Ấy là miền gốm cổ Gò Sành tại thôn Phụ Quang, xã Nhơn Hoà huyện An Nhơn. Bên dòng sôn

Khai mạc triển lãm “Từ gốm Gò Sành đến gốm Quảng Đức”

(BĐ) - Chiều qua (24.7), tại Bảo tàng Gốm cổ Gò Sành Vijaya Chămpa Bình Định (TP. Quy Nhơn), đã khai mạc triển lãm chuyên đề “Từ gốm Gò Sành đến gốm Quảng Đức”.

Nhà nghiên cứu Suzuki Tomomi: Gốm nung làm rung động trái tim tôi

Chiều chớm xuân bên dòng sông Ba soi bóng phố thị Tuy Hòa, Suzuki Tomomi, người Nhật Bản, say sưa phác họa lại chuyến điền dã từ Đà Nẵng đến Phú Yên để được tận mắt chiêm ngưỡng những kiệt tá

QUẢNG ĐỨC – LÀNG GỐM CỔ BÊN BỜ SÔNG CÁI

Lâu nay, giới chơi cổ vật thường nhắc đến một dòng gốm cổ với nhiều nét riêng độc đáo có nguồn gốc từ làng Quảng Đức,

Gốm Quảng Đức - một dòng gốm cổ bị thất truyền

Ngày 29/6/2009 vừa qua, tại nhà lưu niệm luật sư Nguyễn Hữu Thọ, số 3 Tản Đà, TP Tuy Hòa, tỉnh Phú Yên, đã khai mạc triển lãm Con đường đất nung và kéo dài 3 tháng.

Gốm Quảng Đức - di sản văn hóa tiêu biểu của Phú Yên

Đầu năm 2014, cụ Nguyễn Thịnh - nghệ nhân cuối cùng của dòng gốm cổ Quảng Đức - về với thế giới vĩnh hằng ở tuổi 90, khép lại những tư liệu sống về một trong những di sản tiêu biểu trên vùn